Students Raise Funds For Kids With Cancer

“It was addictive. I wanted to continue that feeling. It was such an incredible feeling. I wanted more and more. It became something that I loved.”

Many of us can associate these words with a loved one who has a drug or alcohol problem. Sometimes it’s easy to forget that people are just as capable of being addicted to something good as something bad. The person quoted above is Kate Colgan, the student Executive Director of the Penn State THON. I (Katrina) met her virtually, and her passion for THON positively oozed through my screen towards me.

THON was founded in 1972 and has since become the largest student-run philanthropy in the world. Beginning with 78 dancers who raised $2,000, THON has now raised more than $250M, including $10.6M last year.

From the THON website:

THON is a student-run philanthropy committed to enhancing the lives of children and families impacted by childhood cancer. Our mission is to provide emotional and financial support, spread awareness, and ensure funding for critical research—all in pursuit of a cure. Our yearlong efforts culminate in a 46-hour dance maraTHON.

Kate Colgan started her THON journey in middle school. At the time, her cousin was a student at Penn State and the Executive Director of THON. What Colgan describes above is what many student volunteers for THON experience—the satisfaction of being a part of the robust THON community.

This is usually the part of the story where we in the industry stop talking about community. We leave it with that kind of feel-good statement. But today, we’ll dig into how to translate the “feel-good” into a system that produces people who feel the way Cogan feels. It’s important because those feelings translate into the kind of high-value leadership volunteers, donors, fundraisers, and ultimately the revenue you need to fund your mission.

Fabian Pfortmüller, a co-founder of the Together Institute, has developed a simple question to help determine how strong a community is. “If a person, who is a member in the same community as me, but the two of us have never met, contacts me and asks for my help, how likely am I to help her/him?” How much would you feel connected to them? Would you answer their email? Return a phone call? Go to a gathering they invite you to?

This simple test assumes the following:

The stronger a community, the stronger the shared identity and the stronger the trust among the members.

Trust is actionable. More trust leads to more action.

Given these assumptions, the community’s strength can be measured by the number of engagements community members have with each other. That suggests that forming a robust community must go beyond giving occasional random hugs, praises, and plaques.

How do you set the stage for a robust community to break into full bloom?

There are two required conditions to form a community:

Community members have a shared interest.

Community members have a way to talk with each other.

In the for-profit world, one might be using terms like “engagement creation and scoring” to describe constituent engagement with the organization. You know, counting the number of times people are engaged with our nonprofit. This is different. What we are talking about is community members engaging with other members of the community. Sorry for the shouting bold type, but almost every time we say this, it is misinterpreted and reframed to only include the engagement between the constituent and the organization. That isn’t what we mean. So, throw out your father’s marketing department engagement scoring. It’s not measuring the same thing.

In social good fundraising, the Penn State THON demonstrates the systemization of community—engagement creation—better than almost any organization. Colgan explains, “It’s all intentional and ingrained in the culture—retention, excitement, connection to the mission.”

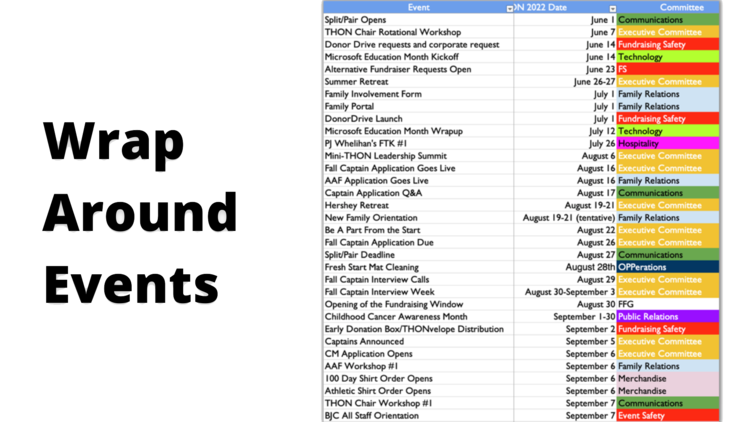

The system’s backbone is a series of events that run all year, a sample of which is shown below. The complete list is 243 lines long, of which about half are events, not deadlines. For example, one line might be, “THON 5K” or “Staff Retreat,” or “Mat Cleaning.” Each of these lines implies a full-bore event and lots of people talking with other members of their community during it. Even events like “Mat Cleaning” are turned into community events through what I can only call “party-fication.” Cleaning products, music, snacks, dancing, people—a magic recipe for building community.

Suzanne Graney, Executive Director of Four Diamonds, the Foundation connected to THON and Penn State, says that THON is “a highly-structured system that produces community members committed to enhancing the lives of children and families impacted by childhood cancer. And oh, they dance and raise millions every year.”

Notable is that Graney does not describe THON as an event but rather as a system. The events scheduled throughout the year give students the chance to reinforce their attachment to their community by being with one another. Thus, they attach strongly to the shared interest—fundraising “For The Kids”—their mantra.

But how does that actually work inside someone’s head? Remember bullet #2 from above? The ability to “communicate with each other” is a primary factor in staying attached and active in the community. Why is that?

Otis Fulton, Turnkey’s social psychologist, explains: “Identity and community are closely-related concepts. In many ways, individuals’ identities are defined by the communities they are members of. For example, political parties, ethnicities, religious affiliation, age groups, social clubs—all are ways we define ourselves. Some parts of our identity are more important than others at any given time, more ‘salient,’ as psychologists say. The more we engage with a community that defines us, the more that part of our identity is reinforced. It’s kind of a virtuous cycle; the more we engage, the more our identity is strengthened, which in turn makes us more likely to engage further. So, enabling community members to engage with each other greatly increases the number of opportunities to express one’s identity.”

You may be reading this and saying to yourself, “Sure, but THON is different from my event, my event series.” Maybe you think that if you trusted your community to run your walk or run, the event would fall short of the goal, or worse, would never happen at all. If that’s what you’re thinking, I blame my lackluster storytelling. Still, if that’s what you’re thinking, you’re very wrong. I know it can be difficult to wrap your head around shifting to a “community” mindset. For example, many of us think of our email list as our community. But, if that’s the case, you don’t have a community; you’ve got a crowd.

So, let’s try making an analogy to help describe what happens with THON:

Graney’s Four Diamonds team will play the role of nonprofit event staff in our analogy.

The student leaders will play the role of your walk leadership volunteers.

Most social fundraising organizations that use an activity to fundraise spend most of their energy on the event logistics. In this typical scenario, Graney and her staff would spend much of their time worrying about the walk itself, running logistics, and recruiting fundraisers and sponsors. But, in the actual THON world, Graney and staff spend ALL their time breaking down barriers and setting up support systems for the students to get the work done. Graney’s team doesn’t run anything or even make meaningful decisions about the community or the event. (Fundraising platform? Selected by the student leaders.) The staff doesn’t touch the dance. Only the student leaders touch the dance. Only the student leaders make meaningful decisions.

Four Diamonds’ system delivers satisfaction to volunteers from being part of a community while at the same time fulfilling other individual needs. Fulton explains: “By releasing control of THON to students and taking a backseat, Four Diamonds leadership also supports individuals’ desire for autonomy and provides opportunities to show competence (to do something well).”

Further, THON uses recognition powerfully and in diverse ways, far beyond giving a t-shirt for raising $100, which I consider the lazy way to recognize fundraisers.

Achieving leadership in THON is a big deal at Penn State—a really big deal. The student body is acutely aware of THON, which is woven into the fabric of university life. Graney says that THON paraphernalia outnumbers Penn State wearables on campus. The THON Executive Director role is highly coveted, as is every director role. Even on its website (please go look at this now), THON celebrates the individuals doing the work: https://THON.org/director-bios/

Imagine a walk that posts on the event site the volunteer leadership of every committee the way THON does. You can probably only imagine it because almost no nonprofit actually does this. Not only do people feel great from the recognition, their identity as a Warrior for __________ (fill in with your cause) is reinforced. Steal this idea now. Steal all these ideas now.

This story is much longer, deeper, more complex. OMG—243 top-level lines! If you should have the chance, corner Graney at any industry event. Her stories are worth holding her hostage with a lovely glass of sauvignon blanc. Call me too; THON stories lift me. Make mine a New Zealand…